This is the second post related to my quest to simplify what I do at training. If you didn’t see the first post, which has activities for attack, follow THIS LINK.

A re-cap of the areas for improvement and design principles …

Areas for Improvement:

- Athlete-Centred

- Their needs … requires assessment; ask them, but provide options (don’t know?)

- Their wants … open or from a list of choices

- Representative

- Percentage of action can be a guide.

- What do they really need now / for the future?

- MUST look and feel like the real game: starts, boundaries, numbers, variation, equipment, rules. Pressure, timing, realistic information vital to skill development.

- Repetition (without ‘repetition’)

- Balance between ‘getting reps in’ and providing randomized problem solving

- Activities: static, transition, multi, broken

- Constraints-led

- Providing opportunities to explore, discover, adapt/adopt

- Constraints are NOT limitations but invitations

- Challenge Point

- Finding optimal ‘learning zone’ (40-60% success?)

- May need differentiated activities to meet needs of all

- Self-Determination, Discovery

- Discovery is most impactful and robust form of learning

- Focus on outcomes. Guide more than instruct. There are ‘wrong’ ways, but there are many ‘right’ ways. Clear objectives will keep them focused. Give time and trust them.

- Question more than tell; questions should not be a guessing game or a regurgitation of cliches; consider Bloom’s taxonomy and don’t be afraid to leave for later

- Mark Bennett’s “Rule of 3” (individual, peers, coach)

- James Gee / Amy Price … missions; challenge, clue, cheat, change

- Early or mid-activity debriefs (teachable moments) more impactful than after-action

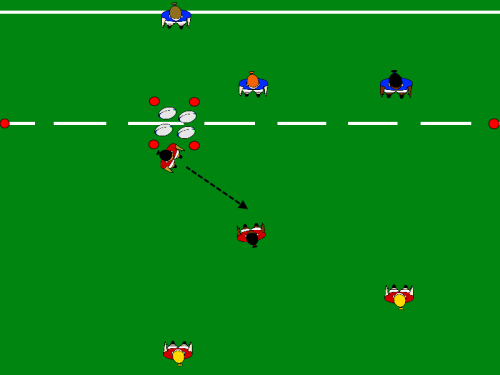

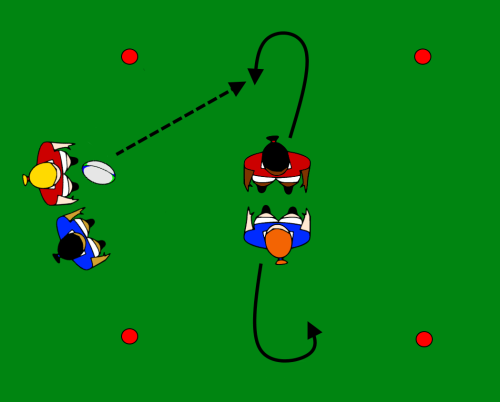

1 v 1

Procedure:

- Attacker and defender stand face-to-face, retreat to own line and come forward

- Attacker is passed ball, tries to evade

- Defender comes forward, tracks, wraps safe and strong; aims to drive back or out

- If defender cannot, can still ‘win’ by wrapping from behind and pulling back

Adaptations:

- Closer = more contact

- Wider = evasion

- Full Contact = incl. supporters to jackal and ruck

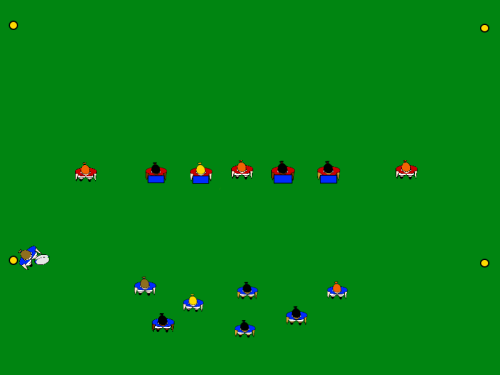

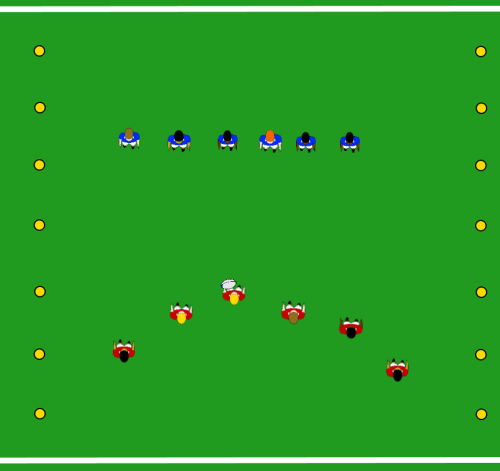

1 (+?) v 4 Unit Defence

Procedure:

- 4 defenders and same/fewer attackers start on opposite lines

- Coach/extra player passes ball to one attacker, and defence comes forward; supporting attackers do a down-up before moving to support

- Defenders aim to take away space, make a tackle, and win the ball back

Adaptations:

- Narrower channel for forwards

- Wider channel for backs

- If focus is more on defensive pressure and coordination, can remove full contact and go wrap = down

- Can join two together, playing the ball from one group to the next group

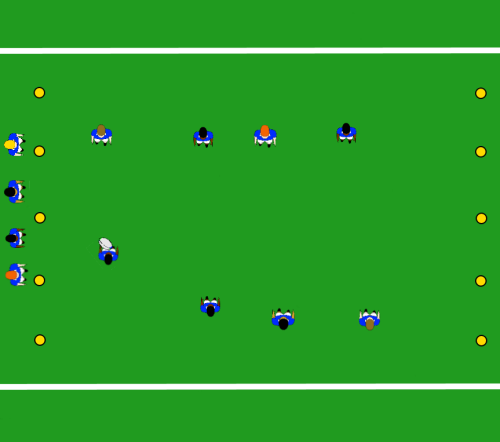

Multi-Directional Unit Defence

Procedure:

- Three defenders start in the middle of a large playing area (cone in the middle is their rallying point)

- Attacking teams on the sides take turns trying to score a try on the other side

- They must announce themselves before moving forward and must wait until the defending team has returned to the rallying cone in the middle

- Defenders can stay in for a set number of attacks or aim to hold off a target number

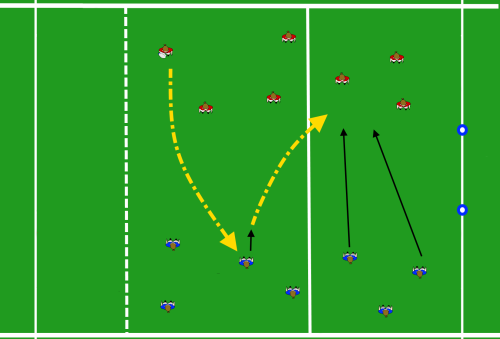

Defensive Pressure Game

Procedure:

- Evenly-matched attackers and defenders face off in a large playing area

- Attackers start with a tap at centre and have 10 phases to score; the value of the try decreases by one point every phase, starting with 10 points from the onset

- Defenders touch/wrap to not just stop them, but win points for themselves:

- ball carrier caught behind gainline (1pt)

- pressure or create turnover (knock-on, thrown forward, into touch, intercepted – 5pts)

- try scored (intercept, turnover recovered and scored without being caught – 10 pts)

- When caught, ball carrier goes to ground and offside line becomes length of their body; defenders can move forward on play of the ball

Whole Team Game:

See: Limited Phase Ruck Game in the attacking activities section … can provide various objectives and/or points as per the Defensive Pressure Game above.