I set myself a challenge this year of keeping the number of activities I use down to a minimum so we’re not wasting time teaching athletes a new one every few sessions. I think these cover all the bases for novice and experienced players and are adaptable enough to include more or less contact, space, players, etc.

For Defence activities, click THIS LINK.

First, some design principles …

Areas for Improvement:

- Athlete-Centred

- Their needs … requires assessment; ask them, but provide options (don’t know?)

- Their wants … open or from a list of choices

- Representative

- Percentage of action can be a guide.

- What do they really need now / for the future?

- MUST look and feel like the real game: starts, boundaries, numbers, variation, equipment, rules. Pressure, timing, realistic information vital to skill development.

- Repetition (without ‘repetition’)

- Balance between ‘getting reps in’ and providing randomized problem solving

- Activities: static, transition, multi, broken

- Constraints-led

- Providing opportunities to explore, discover, adapt/adopt

- Constraints are NOT limitations but invitations

- Challenge Point

- Finding optimal ‘learning zone’ (40-60% success?)

- May need differentiated activities to meet needs of all

- Self-Determination, Discovery

- Discovery is most impactful and robust form of learning

- Focus on outcomes. Guide more than instruct. There are ‘wrong’ ways, but there are many ‘right’ ways. Clear objectives will keep them focused. Give time and trust them.

- Question more than tell; questions should not be a guessing game or a regurgitation of cliches; consider Bloom’s taxonomy and don’t be afraid to leave for later

- Mark Bennett’s “Rule of 3” (individual, peers, coach)

- James Gee / Amy Price … missions; challenge, clue, cheat, change

- Early or mid-activity debriefs (teachable moments) more impactful than after-action

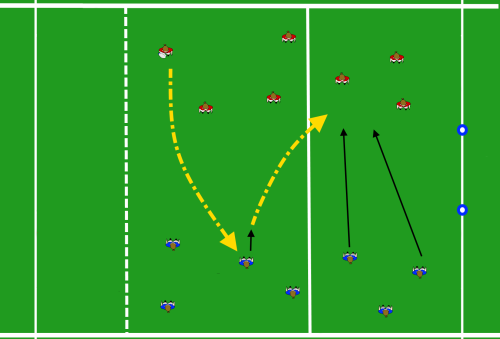

Tool Box Drill

Procedure:

- Ruck area with ball straddles 5m line

- Defenders start at back cones

- Attackers aim to get over gain line using full ‘tool box’ of options

- Numbers should be even or +1 attack

- Teams alternate left/right, each side having different widths

Adaptations:

- Touch = high pressure, skill, timing

- Wrap = allow for tight spaces, contact options

- Defenders can be delayed with a down-up upon arrival if attackers need help

4 v 2 / 2 Open Field Attack

Procedure:

- 4 attackers start in the middle of a deep and wide playing area

- 2 defenders wait at each end, moving forward when attackers start in their direction

- Attackers aim to score as many tries as possible in a set period of time (competing against other groups)

Adaptations:

- If numbers aren’t balanced, extra attacker first, extra defender next

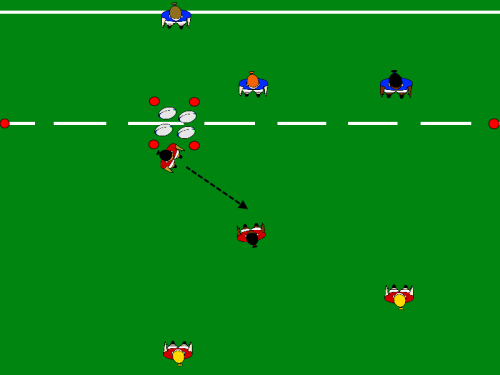

One-Two Punch Scenario

Procedure:

- A group of attackers start with backs to the playing area

- Defenders align themselves differently each time in the middle of the playing area

- On scrum half’s call, attackers turn and decide on first phase to either break through on set up next phase

- Only get two phases, so need to be purposeful

- Defenders can be a mix of bags (stop attackers by holding forward progression) and those without (stop attackers with touch or wrap)… can be wrap/touch and coloured shirts if not with bags

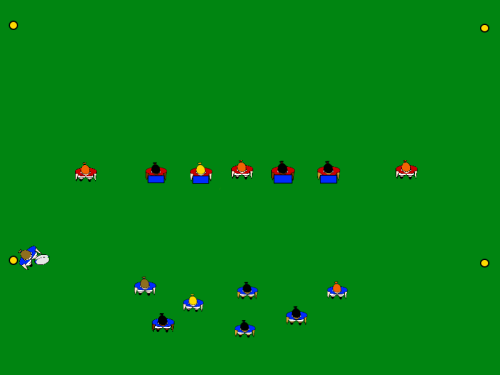

Limited Phase Ruck Game

Procedure:

- Two evenly-matched teams square off and play touch/wrap for a limited number of phases (3-6 causes teams to be purposeful in their approach, and is common average for amateur teams)

- Can start from lineout, scrum, or tap penalty; should be refereed to ensure laws followed

- When contact is made, ball carrier must go to ground. Defender(s) making touch/wrap must also go to ground, but can jackal if no support has arrived once back on feet.

- Can require one or two attackers to secure ‘ruck’ or allow to make that choice; defenders not involved in the tackle can come through gate to contest possession.

Adaptations:

- Can alter points system for desired outcomes, alternating teams for a set number of goes (example: tries from kicks worth more)

- To incorporate offloads into touch game, give carrier one-step/one-second to do so before requiring to go down

- Can play to ‘super powers’ of various types of player:

-

-

- Power players require a double touch / tap

- Elusive players get three extra steps if tagged/wrapped from behind

- Distributors win ‘free phase’ (not counted against limit) if they / player passed to get over the gain line

- Support players win ‘free phase’ if call for an offload

-

-

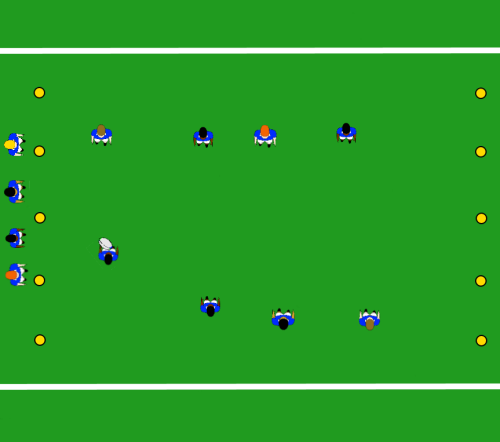

Rapid Fire Touch

Procedure:

- Two teams (3 or 4) start in the middle of a playing area. Attacking side taps and runs.

- If defender(s) touch/wrap ball carrier, or attackers knock-on, throw forward or go into touch, defenders take possession and run to nearest goal line (all must cross!). They start attacking immediately.

- As initial attacking team leaves, the next group waiting at the side enters and act as defenders.

Adaptations:

- Can make ‘double touch’, meaning that ball carrier tagged by one defender can keep going (but not score) until touched by a second defender

Kick and Counter

Procedure:

- One team starts play by kicking off to the other with a drop kick

- Teams in possession have 3 seconds to run and pass, but must kick the ball within that time (called out by the referee) or concede a turnover

- If a player is touched/wrapped by an on-side defender in this time, they also concede a turnover

- Tries are worth 5 points, penalty / drop kicks at goal (if playing full field) worth 3 points (could even allow penalty goals if playing half-field!)

- Referee necessary to call time and make sure players are on-side, otherwise abiding by the laws