In the summer, while touring around Germany, I read a book about the history and evolution of American football tactics and formations called Blood, Sweat and Chalk by Tim Layden.

Years ago, I stumbled upon an article that covered this (which I haven’t been able to find since!) and it made me think about rugby’s evolution and the use of tactics. I do have a great book called Developments in the Field of Play by JJ Stewart, but it seems there was more innovation in the first 100 or so years of rugby than in the last 50, and largely because of law changes, not because coaches dared to be different. At the time of reading these, I didn’t think there was as much creativity in rugby as there could be. In the last couple of years, I think top level rugby has become even less creative and when I again hunted for the article, I stumbled upon Layden’s book. It covers about 100 years of changes from the pre-passing days to the current era. It admits that football has some of the same ‘copycat’ issues that rugby has, especially when an innovation proves successful, but it also suggests that there are still varied approaches and that the ‘old way’ occasionally gets re-used. Rugby doesn’t have such a wide range of historic approaches like football, and I’m not advocating rugby become very rigid like the American game can be, but when was the last time you saw, say, a dribbling rush in a rugby game? Do you even know what a dribbling rush is? (Forwards would kick the ball along the ground to advance it because you can’t be tackled if not carrying it!)

I’ve been thinking of some more creative approaches to playing, inspired by old rugby manuals, and this book has further emboldened me to see how they’d do in today’s game. What follows are my reflections from Layden’s book that might help you also make the game more interesting and rewarding for your players.

“Their work is equal parts science and art – the science of outmaneuvering an opponent like a military field commander and the art of understanding the subtleties of player’s abilities.” (9)

In expanding upon the above quote, Layden adds that while ‘chalk talk’ involves the study of concepts, that “the game isn’t played by concepts; it’s played by human athletes.” (10) This is a great reminder that no matter which point of the spectrum you fall, between ‘just the basics’ and ‘extreme creativity’, you still have to select approaches that suit the players you have, and that can change year to year. Professional teams – and some might say even representative teams (but I’d argue, for junior grades, that’s wrong and inhibits growth) – have the ability to select the athletes that fit the system, but the vast majority of us don’t have that luxury, nor do we have the time to mould raw athletes into a specific system when we can simply select strategy and tactics to suit them.

“Football innovation repeatedly proves itself the product of coincidence, of personalities thrown together and forced to improvise strategy for the sake of survival.” (27)

Layden tells the story about how, possibly, the ‘Wildcat’ formation, which snaps the ball to a non-traditional ‘quarter-back’, was born out of a coach having an incredibly fast receiver who’d played quarterback in junior high. He hadn’t known it was similar to the ‘Single Wing’ formation used decades before that had fallen out of fashion. The ‘unconventional’ approach worked for the boys he had, as it did for the coaches who employed it way back when, showing how working with, not against, constraints can produce something fantastic. He also talks about how good coaches see better roles for players and encourage them to play elsewhere when the stereotypical or traditional (i.e. “I’ve only ever played this position!”) might no longer suit (pp. 54-55). A high school quarterback who was too erratic to deal with defences / system at the next level found a new home and success as a wide receiver. The less-flashy backup ended up being the perfect steady QB to unleash the creative star. I’ve seen this several times in rugby where coaches put their best players at 9 or 10. Instead of putting them in roles where their space is limited, opt for competent ones who can deliver that ball in space. I suspect that’s why rugby League hookers act more like Union scrum halves, allowing all backs to operate in space. One of my teams allowed our incredibly elusive scrum half to do her thing in space with forwards making short passes to her from the breakdown, rather than force her to dig out every ball.

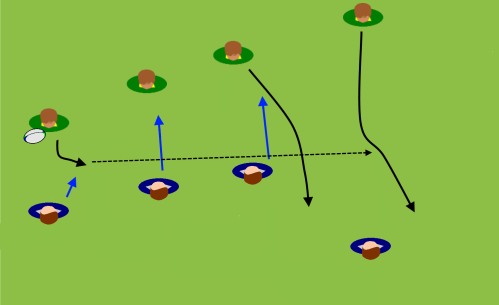

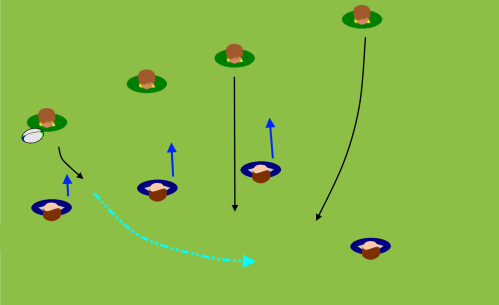

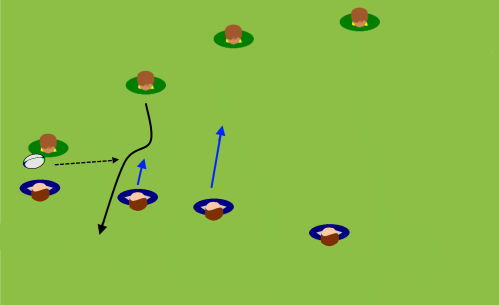

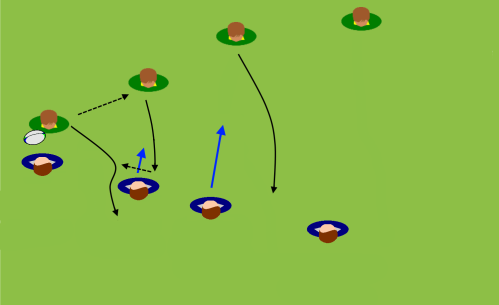

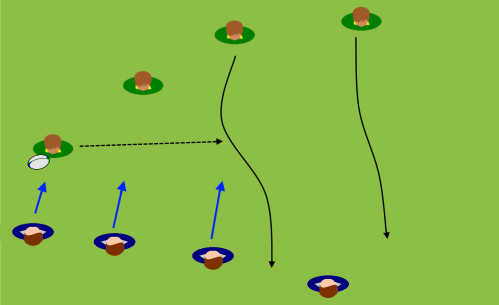

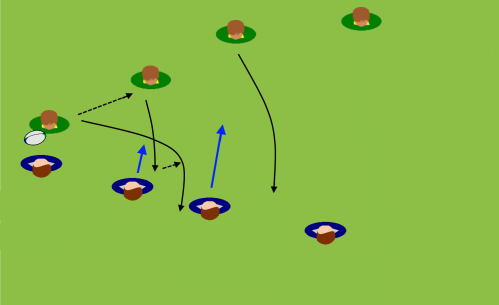

From innovation comes further innovation. Coaches who like the principle behind something new or a certain aspect of a creative approach can either tweak it to suit their own players or dream up something different having been inspired by it. One example given in the book looks at how the tight ‘Wishbone’ formation was altered into the wider ‘Flexbone’ formation (61), one relying on concentrated power with the other more on exploiting space. Football coaches, no matter the formation, always have many options of them. One of my critiques of top flight rugby at the moment is how the rigid systems approach claims to have options, but really the options are very few (and they are rarely ‘opted’ upon). As such defences tend to have an easier job when dealing with forwards, in particular. Pods almost always crash into the line with the first receiver, occasionally play out the back, and rarely ‘tip on’ to a second forward. Rare do we even see some of the intricate running lines and passing options seen in League, which, incidentally is where Union got the idea for dummy runners and second man plays. If every phase – including small groups of forwards – featured players in a dynamic shape, each with the potential to get the ball and do something with it in hand, defenders have a much more difficult task. The hesitation, over/under commitment, reactive rather than proactive decisions imposed upon defences by creative and dynamic attackers gives them the initiative. Doing the same thing everyone else does 75% of the time means you’re only, really, hoping for a rare mistake or to win a boring and exhausting battle of attrition.

Taking a creative approach to play is something many school and club coaches shouldn’t fear doing. What’s to lose if you’re already a team that’s perennially in the bottom half of the table or if jobs / recruitment aren’t affected by results? Hell, your players might actually understand the game better if they’re exploring how to do something different than the rest! To innovate beyond the status quo, you’ve got to know what it is. From the formations examined in the book, it seems that most innovation in football has come from college and even high school programs that took a risk or created a solution to a problem. Don Coryell’s San Diego State team, which couldn’t compete with local rivals to sign the best runners and blockers coming out of high school, revolutionized the passing game because he was able to get decent (possibly small?), underappreciated quarterbacks and receivers from junior colleges. Their success with the throwing game, when most others ran the ball, made me think about how many coaches discourage kicking in rugby. Yes, some players kick when the run option was on, and keeping possession is more likely with safe carrying and efficient ruck. But teams that are known to kick can face reduced pressure if the defence is not sure when the kick will come, some defences do not how to deal with kicks, and others will kick it straight back, allowing for a nice open counter-attack with defenders spread out all over the place.

The throwing game in football seems to be en vogue at the moment, and Kurt Warner’s statement on why he likes it also had me thinking about kicking in rugby. “The design of the offense was to continually put pressure on the back end of the defense. It was all about getting chunks of yardage.” (88) Bill Walsh’s use of short passes to expose blitz defences also seemed to have had both a reactionary and exploitative effect. In between going for the big scoring play and grinding teams down through dominance is achieving moderate gains through short plays 4-8 yards at a time. I’m someone who doesn’t put a lot of time into set piece plays and I’m also not in favour of the boring, attritional approach of one-out rugby and pick-and-goes. Like Walsh’s short throws, I challenge my athletes to break the gainline on every single phase – wherever that may be. They can follow a pattern if nothing clear and obvious presents itself, but as soon as possible, they should get back to a state where we’re breaching the gain line and forcing the defence to scramble a few metres back to re-establish their line. This perpetual state of disorder will eventually cause them to give us an easy scoring option, exposing uncovered space, a mismatch or an overlap. One of Coryell’s credos in this sense directly applies to rugby: “Never pass up an open receiver. If he’s there, stop ‘reading’ and throw it to him.” There’s no need to follow the script if something better is immediately apparent. Rugby has even more advantages in football in this regard, because we’re not limited by four downs. Going for short gains works everywhere so long as you win the ball back at the breakdown. In the recent November series, I was disappointed to see the All Blacks not do what they do best until late in the game – get behind the gainline by going wide quickly. Instead, they bashed it up the middle a metre or so at a time, which allowed the well-disciplined Irish defence to reorganize themselves and be ready for the the next one. Ireland may have only allowed a few more metres when the All Blacks went wide, but there’s a big difference in attacking defenders who’ve had to turn and run back and aren’t quite set / focused compared to running against those who’ve only had to take a couple of steps back and to the side, keeping your next wave in their field of vision the whole time. More ambitious moves that keep defenders guessing, giving up several metres at a time, and well-placed and chased kicks can offer the same sort of opportunities to turn pressure into better attacking options.

The other major takeaway I got from the book was related not to on field stuff, but off-field collegiality. There have been some immense rivalries and we’ve seen seemingly hard ass football personalities in the media, but the book suggests that much of the American football world is open to sharing ideas. Thinking back on my 18 years coaching, I can’t remember a time that a coach from another school or club shared what he or she was doing, and admitted to myself that I’ve only been doing it in the last few years. We talk a lot about rugby being this ‘gentleman’s game’ and having some kind of aura of inclusivity, but too often we’re going against that by protecting our own interests and not thinking about the bigger picture.

“Football socializes. Everything belongs to everyone else, especially diagrams on a board or the plays on a film.” (139)

Great coaches know that there’s always room to improve but how can any of us improve if we’re not challenged? I’ve seen programs dominate locally year to year, but then get shocked when they attend a tournament elsewhere? If you care about development and doing well at other levels (not to mention ensuring your players can go anywhere and be successful), then it’s up to us to be more open and share so we can raise our game. Our region challenges others to raise their game, and our province challenges others to match us, making the national team as strong as can be. I believe that’s the main reason New Zealand is so great, but I do wonder if that may wane a bit if the top schools continue to poach talent from the have-nots? I suspect they’ll be okay, though, because All Blacks and great pros continue to emerge from these schools, suggesting that their coaches still know how to develop good players even if they don’t have a wealth of talent at their disposal (especially given that rugby is a late development sport… how many of those school poaches go on to be great players would make for an interesting study!).

In football … “Coaches find each other. They hang out together and eat together and drink beer together… It is their way of finding normalcy. But it’s also a way of staying in the endless loop of innovation. Friends do not hide discovery from each other.” (149) Layden talks about coaches holding clinics for coaches and sharing resources even while they’re still using them. There’s a money-making aspect to it, sure, but there’s also the belief that letting others know what you’re doing will force you to do it better and develop ways to combat the ways your opponents would defeat your strategy and tactics. As suggested by the analogy offered at the start, the shrewd general is aware of how his enemies might defeat what’s made his army successful – the science of battle. He is also astutely aware of the subtle ways that his subordinates and troops on the ground operate, which is the art of leadership. I think the barriers to knowledge sharing and innovation in rugby are breaking down via social media and YouTube. With them, you can learn about a lot about how the top-level approaches rugby, but I think we can do a lot more to both share with the grassroots level and also not be afraid of trying to do something completely different than the pros. Whether or not your innovative approaches become the next big thing in the sport or even over-come the limitations you face, the process of examining deeper demands, needs, and possibilities will help you and your athletes understand the game so much more and allows them to benefit from a richer experience of exploration and discovery.

Read Full Post »