I’m a few days away from my first session with a new team and I’ve been watching, listening, reading and writing sports and coaching for a few weeks now in preparation. My next few posts are going to condense and outline some of this – also building upon my many years of experience – as a resource for those athletes who’d like to read my thoughts. Hopefully coaches who read this blog will also take from it what they find useful.

Attacking Focus

1. Play Head’s Up Rugby (Low structure imposed upon, high assessment and coordination demanded of players.)

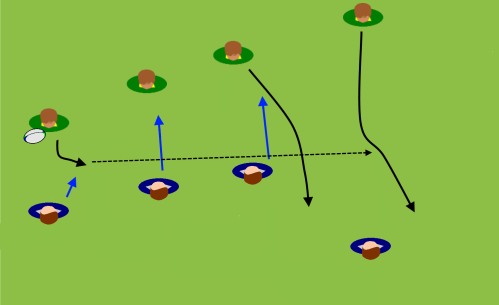

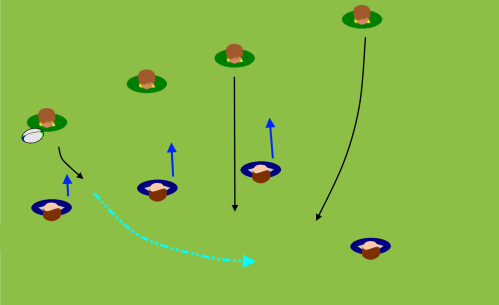

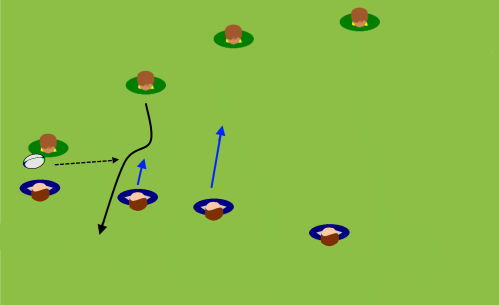

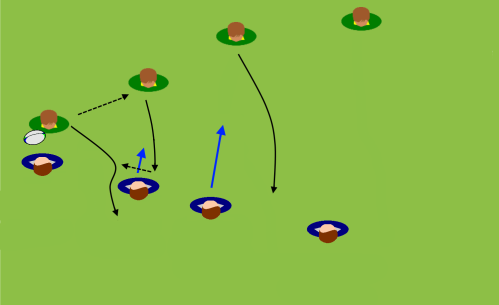

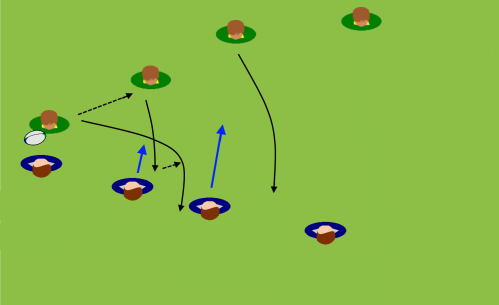

a) Seize and exploit the ‘easy opportunity’ (ex. over-lap, gap, strong vs weak, fast vs slow, poor alignment, etc.)

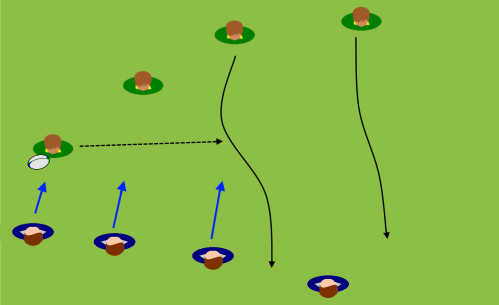

b) Create an opportunity by using a simple move (can be simple as a sudden and sharp change of direction that manipulates the defence and allows support players options, or a multi-option snap play like a loop or a blocker line)

Before the defence re-aligns, look for a new ‘exploitable’ opportunity. This is a simple cycle where some players will be better at scanning and seizing but will have options to create opportunities if nothing easier is immediately apparent (not just from their scanning, but also from team mate feedback!). While I will train everyone to enhance their ability to anticipate and recognise patterns and visual cues, players not so aware can always start from b), using the attacking tool box mentioned in my previous post.

2. Maintain a quick tempo and play to our strengths

Playing in a provincial Premier League means we’ll face very strong and well-coached teams. I expect to especially see strong defending teams as those aspects are typically easier to coach (as seen in the recent Women’s Rugby World Cup!) We are lucky to have plenty of options in terms of speed, power, finesse, and game smarts. In conjunction with playing “head’s up” – and sometimes as a default option when there are no easy opportunities / creative efforts are being shut down – we can proactively and patiently string together phases in a logical way. Dominating the contact area to win quick ball, with good coordination and communication, means we should have a lot of people in good positions to keep the tempo up and prevent the defence from getting properly re-aligned. From this situation, defences break down and get us back to the ‘easy opportunity’ situations. For example, consider how even a 3m penetration with quick ball can catch defenders off side or unsure of who they’re supposed to be covering, or how a few phases in one direction with a wide move in the other could find speedy players against unfit ones. Not only do playmakers need to be aware of these possibilities, but all players should be assessing simple things like “Do I need to go in that ruck, or can I stay here and be part of the next phase?” Little ‘rules’ can be devised which fit the players you have – in our case, we’ll have a lot of options as we have a big tight five, mobile back row, intelligent midfielders and speedy outside backs. The trick will be to play to the ‘best’ strength at a given moment – something we will continually work on in game-like practice.

Important Factors in Achieving This:

- Awareness – at all times – scanning / communicating / listening (playmakers use info to make decisions)

- Work-rate – whoever is aligned first has the initiative. In contact, the fewer people needed to win a tackle contest, the more people we have for the next phase.

- Alignment considered – we need more than one ‘layer’ to ensure we can be proactive, but also reactive (i.e. a strike runner can have a go at space, but if the timing is off or the defence adjusts, we need a ‘back door’ outlet to keep the play alive and not resort to something that’ll lead to slow ball). This means more than getting into good positions. It also means that players have to consider their actions. The two most common: forwards jogging to rucks that are already won to stand beside it doing nothing; backs who run up flat when the play has been halted much further inward to then have to back pedal into a good position to receive the ball on the next phase. To maintain a good tempo with sufficient numbers, players need to be efficient in their alignment (it also saves them from wasting energy where they’re not needed). They should also begin to recognise when the defence is on the back foot (allowing us to play flatter and have a quick go at the line) or on the front foot (maybe forcing us to have a plan to cope with defenders ready to pounce).

- Ball movement – more than just quality and accuracy, timing of the pass is vital to the success of a move. An early pass gives someone else in a better position the time and space to use it. A late pass should be putting someone into a gap. A pass too early, without threatening the defence, can simply allow defenders to push across and cut off our options. A pass too late can be forward, at the wrong target, too hard or otherwise useless. Two quick passes can get us into more space in a hurry. A dummy pass can get us through a gap in that ‘black hole’ area behind a ruck.

- Thoughtful running lines – straight running fixes defenders in place and preserves space for team mates. Sharp and sudden changes of angle can exploit space and the ‘soft shoulder’ of the next defender in line. Running too early can get you ahead of the play; too late invites the defence to take space away. Remember that a line can be a great decoy, so make sure not to ‘demand’ the ball when you’ve drawn the attention of two or more defenders. Passers also need to consider this and select a better target.

- Strategic considerations – What’s the score? What part of the field are we in? What are the conditions like? Can we get enough support there? Can they cover kicks? Are they better/worse than us at the scrum or lineouts? Is it wise to have a shot at goal or rely on quick taps? Do we need to get the ball into the hands of our key players more or make a better effort to stay away from a certain player / unit in their team? … these are all strategic considerations that can enhance or ruin our chances of scoring.

- Focused roles – more than our individual strengths, consider your best role in attack. Are you a play maker who sees opportunities and passes well off both hands? A power runner who can make holes and drag several defenders in? A speedster who can burn defenders with pace and/or step around them? A strike runner who has a well-timed crack at space in the line? Or an equally-vital support specialist who does more than ‘hit rucks’, recognising when others are about to break the line, getting into good positions to call for and receive a pass? (Maybe a combo of more than one!)