During the Wasps v Leicester Tigers match yesterday, Tigers’ lock Will Spencer was shown a red card for a high tackle that made forceful contact with the head of Wasps’ hooker Tommy Taylor. Without getting into the social media storm about whether or not it should have been (which angered me as, for the sake of player safety and forcing change, it HAS to be nothing but…), I thought I could address those people who questioned what a 6’7″ player (or any player) could do when caught in a position where it’d be very difficult, if not impossible, to avoid delivering a high tackle.

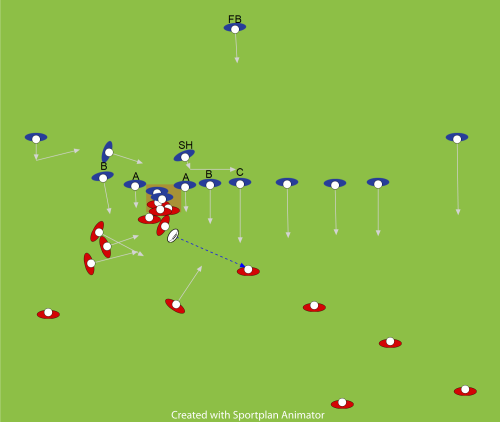

First, here’s the incident:

Firstly, I think it’s important that we stop talking about rugby as being a ‘collision sport’. In some regions / teams, it certainly looks that way with ball carriers running straight into contact and defenders launching themselves into tackles. I recently heard a pro player say it was a ‘game of inches’, which no doubt comes from the NFL and the film Any Given Sunday, but it’s really not. Rugby is a game about possession. It’s really only become a battle of attrition because teams haven’t the ability / skill to evade and cleverly unlock defences and that (frustratingly) the law enforcers allow so many transgressions at the breakdown that it’s not worth contesting much of the time, so they spread their defenders out and offer no clear opportunities for the attack. With referees favouring the attacking side in tackle contests (rucks, mauls), it’s also fairly easy to string 10+ phases together of crash balls where the supporting players immediately seal off.

In addition, rugby league coaches have brought to union the ‘big hit’ and swarming defensive structures that dominate their code. It seems all I hear people talking about when it comes to tackle training is making the dominant hit that drives a ball carrier back. This technique certainly has its positives (get defence on the front foot, knock loose the ball, tackler lands on top so can contest easier, etc.) it doesn’t have to be the only way. When it comes to player safety, it’s been proven that the tackler going high is more likely to suffer a concussion than the carrier and than if using a lower and more passive hit. I have seen people get knocked out from making low tackles, too, but the data from pro rugby shows that high is more risky.

Accidental high tackles are still going to happen, but what needs to change is the mentality that lining a ball carrier up for a crunching tackle is the primary goal. It should be ever-present in the mind of tall players, especially, that a smaller player is going to offer a greater challenge. In the Spencer / Taylor case above, people were (I think deluding themselves by… ) saying that Taylor ‘ducked’ into the tackle. There’s no active ‘ducking’ at all; his change in shape came as a result of his attempt to pass. You can see the same dip in body height in Sapoaga as he passes to Taylor. If you’re still not sold on that, the other way that Taylor’s height changed is upon simply realising he’d been lined up for a big hit by an approaching giant of a lock! These are things that tacklers must be aware of, approaching every situation not as a player-possessed, but as a mindful player who can predict and read a situation and use the best option, even in a split second.

So what could Spencer do? Admittedly, he was committed so it’d have been very difficult to do anything else. He didn’t really ‘launch’ himself, but there is force applied that may not have been necessary. He could have better read the situation and opted for a tackle less-forceful. Below is another, not-dissimilar incident where there wasn’t much time to change but with greater awareness and training, a different outcome should have been possible.

Tu’ungafasi leans into the hit and collides with the Frenchman’s face and his own teammate’s head. Better communication with his teammate and recognition that Cane was already attempting the tackle should have triggered in Tu’ungafasi that he didn’t need to put in a big hit. Trust is so very important on defence this is a great example of where the double hit wasn’t needed; Cane was close enough (and certainly capable enough) to wrap up Grosso, leaving Tu’ugnafasi in an excellent spot to jackal / contest possession. For me, the low passive or low chop tackle is sorely under-used, especially when teams have so many capable jackallers these days. A big hit more often puts the ball back on the attacking team’s side, while a low hit more often has it first presented on the defensive side and with the carrier having to fight through the downed tackler to lay the ball back.

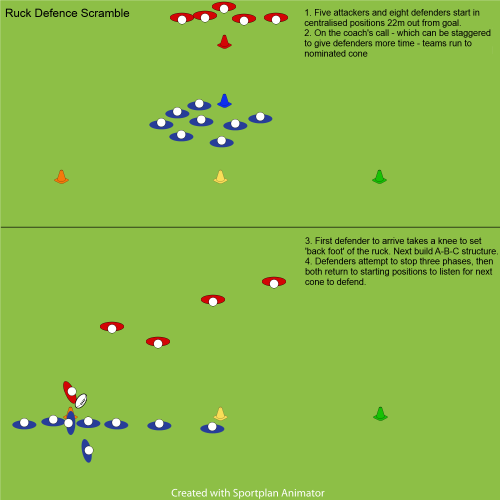

Again, rugby is a game about possession. When introducing defence to a team, I always ask the question: “What’s the aim of defence?” Often, the answers I receive are: to stop scores, make tackles, etc. but the primary aim of defence is to get the ball back, legally, as soon as possible. So the first step toward changing the culture of the ‘big hit’ (something that’s only a recent trend, despite some saying that red cards reflecting a greater focus on player safety are ‘ruining the game’ … but didn’t we all learn to tackle low when we were young/new?) is making players more aware of their actions, the actions of opponents, the most important aspects of playing defence, and appropriate technical application for the situation at hand. This is the one area in my training sessions that I continue to ‘drill’ – not in long lines, but in pairs or small groups. The aim is to give players as many reps as possible at reading body shapes and getting their own positioning correct, often without full contact, so they can be more aware, safer, and use the best techniques to make not only the situation but also their abilities and body types.