In my first post related to the recent Wasps v Leinster match, I looked at Wasps’ defensive issues around the breakdown. In this post, I will examine some issues they had away from the breakdown that led to Leinster tries. My analysis and tips to avoid the issues will follow each clip.

CLIP 1: Recognition and Changing Tactics

Here we see Leinster make great use of Johnny Sexton’s signature move – the loop. He’s used it countless times for Leinster and Ireland, so right off the bat, Wasps have no excuse for failing to adjust to it.

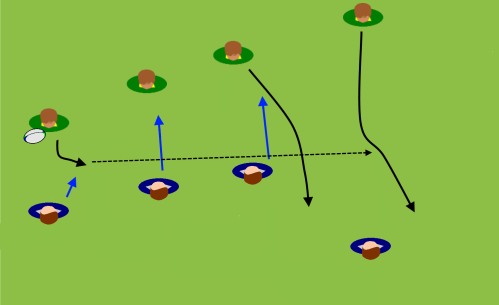

As the ball is passed, we can see that Wasps are evenly matched with Leinster, each having four players. Sexton has turned his whole body to pass and is already following the ball. This is a clear indication that the loop is a possibility, if not a certainty given the personnel involved. When the clip pauses again, we see that the Leinster forward has passed back inside as soon as he’s received the ball. The Wasps forward mirroring Sexton should be calling for a push here because the loop is now clearly on, but his two teammates have dropped their backsides and frozen on the big forward. He’s completely out of the play now so, instead, they should be pushing beyond him to pick up Sexton wrapping around and the outer threats. The lankier of the two (#6) rushes up but Sexton makes his pass. The bigger defender is too slow to catch up and the winger is left to face a three on one. Before I move on to the next issue, if the player mirroring Sexton had called a push defence, the three players outside him could have stayed connected and contained Leinster toward the touchline.

Wasps’ winger starts jockeying backwards to buy time for support to arrive and his fly half does show up to help. What they fail to do, however, is actually get connected to hold the Leinster attackers there or force them wide with a drift. The winger is still backpedaling while the fly half comes forward, getting himself into no-man’s land. Leinster’s prop makes a great dummy and pass around him to free his teammates. If the fly half had better communicated to the winger, they might have stopped the attack there.

Simply, defenders need to anticipate / recognise attacking threats and communicate options / changes to stop those threats. As soon as they lose their coordination and connection (i.e. keeping shoulders in line with each other to create a defensive wall), attackers can easily pick holes to get around, through or behind them.

CLIP 2: Tactics, Responsibility and Trust

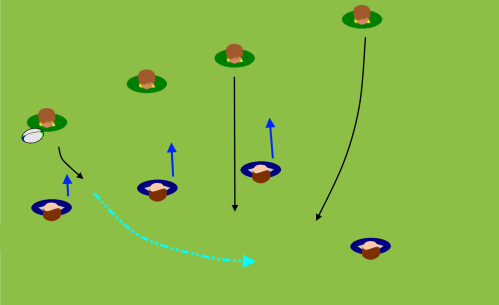

Teams that attack with a conservative one-out, same-way pattern are typically hoping to occupy the defence in an area to create an overlap in another area. By pounding up the middle, they hope to eventually find a moment when they can outflank the opposition out wide. Defenders need to fold around the breakdown quickly, with the outside defenders moving further out to maintain line integrity toward the touchline. Players work quickly and communicate responsibility in transition to ensure gaps are covered. It’s easier for the folding defenders to come around the breakdown to the near side and push teammates out, rather than run behind those defenders and get wide themselves.

Given that the strategy described above is common in rugby, when the clip pauses, the defenders around the ball carrier could have been better at re-aligning themselves. Leinster’s ball carrier isn’t a major threat and is suitably covered by the defender in front of him, but the outer defender (with the scrum cap) needlessly joins the tackle. Instead, he could have stayed out and protected the gap, then slid out as the two other defenders folded around. His act leaves the next phase without someone who could have shored up their line.

The two folding defenders are in a good position and ready to come forward, but the player outside them (third out, with a beard) is both offside and guilty of ruck-inspecting. He hasn’t properly assessed the threat in front of him until the ball is passed. When the clip is paused again, Wasps are in a pretty good position to defend the unit in front of them, but as the play unfolds it’s painfully clear that they are not coordinated with each other. Leinster opt for a dummy runner + pull back play which could have been forced wide if Wasps had started an aggressive drift as soon as the scrum half passed. The defender with the big hair should have pushed out hard on the receiver, with the bearded defender taking the dummy runner and the fly half looking out for the deep option. Instead, the one with the big hair passively holds his gap, the bearded defender gets caught in two minds (focusing on both the passer and the dummy runner, taking neither), and the fly half pinches in on the dummy runner, allowing the deep option to swerve around him into the gap.

Defenders need to be aware of their opponent’s strategy – and most teams have a clear one these days – so they can anticipate patterns and plays, stopping them before they come to fruition. By working hard off the ball to get into position and not over-committing where not needed, defenders can maintain the defensive line across the pitch and have time to plan for the next phase (to act, not just re-act). As the ball is played, defenders need to aggressively move into position to deny the attacking team options, force them to make errors, and/or get into positions where the ball can be won back. If teams passively go about re-aligning and be exclusively reactive rather than proactive, then good teams will be able to attack as they wish without pressure. Finally, taking responsibility, communicating intent, and trusting teammates are essential components of effective team defence.